Marcus [Valance], Property Week’s photographer for our trip, climbs out of the car, pops the boot and begins assembling his equipment. My mobile trills. It’s Liz [Hamson], my editor, and she gets straight to the point: “There’s breaking news – I think you need to hear this.”

After a couple of sentences, I gesture to Marcus – he needs to hear this too. The BBC is reporting that the French government’s plan to raze the southern part of the Jungle to the ground has just been granted permission by a court in Lille. Officials at the Calais prefecture are promising that public areas such as places of worship and schools are to be spared and that the clearance will be a “humanitarian operation”.

The next 24 hours will demonstrate the Calais authorities’ promises to be wide of the truth. Within days, proclamations from the national government that no bulldozers will be used and people won’t be forced from their homes will also prove false.

The gentle smoke drifting from bonfires will be replaced by billowing plumes from tents and shacks being burnt down as much of the southern section of the camp is dismantled or destroyed. Some of the refugees will start decamping to other sites, including Dunkirk.

Today, all that is still to come. While no one would call it home, the Calais campsite remains a functioning community, with an economy of sorts and a range of amenities recognisable to any city dweller: homes, shops, medical facilities, a school and even a theatre.

Welcome to the Jungle, where life goes on, but fun and games are thin on the ground.

Long-running battle

The camp has existed in one form or another since 1999, when a migrant reception centre was set up by the Red Cross. Since then, it has grown, been razed, risen again and changed location on numerous occasions. What is now generally referred to as the Jungle occupies a large tract of land about two miles east of the port of Calais and next to the motorway – immediately obvious to anyone embarking on a journey by ferry between Calais and Dover.

Over the past 17 years, the French authorities have been hostile to the presence of the camps, and have made several attempts to shut them down for good – to no avail. The latest court order allows for an area the prefecture claims to be home to 1,000 people (charity Help Refugees puts the figure at 3,455) to be demolished. It is the latest salvo in the long-running battle between the state and the migrants.

This is the area of the Jungle Marcus and I are contemplating entering when the call alerting us to the court order comes through. There are half a dozen police vans on the stretch of land between us and the dunes at the camp’s border and policemen are standing around in informal groups chatting and smoking cigarettes. Neither their attitude nor their numbers make them seem primed for action.

We are, though. It’s time to see the place for ourselves while we still have light. We stumble up and over the dunes and into the camp itself, passing volunteers and migrants watching the police watching them, and continue up the main ‘commercial’ drag that runs north-south through the Jungle. Middle Eastern and North African music sounds from several of the buildings we pass.

Falling into conversation with people on the dirt-and-stone track, it quickly becomes obvious that on our first trip into the Jungle, we will be the ones being asked the questions. Word of the court order has spread, and people mistakenly assume we will have information on when the authorities will move in.

A middle-aged Pakistani man approaches. “Excuse me, but what is happening about the camp?” he asks politely. “Some people are saying the camp is closing. It’s very difficult for us. What is the solution?”

I don’t know, I reply. The man, who tells me his name is Zakar, asks another question, this time more plaintively: “How much time do we have? One week? Two?”

The estimates will soon prove wildly optimistic, not that anyone other than the authorities knows that yet. We approach a group of young men sitting around a campfire to keep warm. They are from Eritrea and are happy to talk but not to be identified. One poses for a photograph on his mountain bike. I ask what the group will do if the authorities move in. “We will fight,” one of the bike owner’s friends replies.

While a minority ultimately will, at the moment most just seem resigned to the camp’s closure after weeks of increasingly tough language from the prefecture. Their main concern is how much time they will have to get their possessions together and where they will go next. As one camp volunteer says: “I think there is a level of acceptance now.”

By this point it is dark and we head back to the car and our hotel down the road. Spotting an Ibis across the street, we head over thinking the rest of the press – some of whom have been covering the Jungle for weeks – will be there. We’re right. And they are preparing for the worst.

Neil Henderson, the BBC’s main man in Calais, introduces us to his security consultant, an ex-army man with a chest that if prodded would not recede a millimetre. Underlining the seriousness of the situation he believes is unfolding, Henderson produces a gas mask. Marcus and I exchange bemused glances, but within days of our leaving the camp, Henderson will be needing that mask.

At first light, we’re back in the Jungle and trying to get to the heart of how the place operates. The police build-up is beginning but doesn’t yet seem to have reached critical mass. One question strikes me immediately: where are the international NGOs? With the notable exception of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), there isn’t a single household name operating within the camp’s boundaries.

Even MSF has only been here since September and it is only providing ‘basic healthcare, physiotherapy and mental health services’. This seems as bizarre to Marcus as it does to me. He has spent the previous few weeks volunteering in Greece, patrolling the beaches and helping guide refugees to shelter. There, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is leading the rescue mission and ensuring the vast majority of people receive clothing, food and shelter. The situation, he says, is desperate but organised.

It turns out that the difference is that major NGOs have to be invited into a country to commence operations. In Greece the government welcomes outside support, whereas in France there is an unwillingness to acknowledge a problem even exists.

The assumption among volunteers in the Jungle is that MSF was only asked in to prevent a measles outbreak turning into an epidemic and to mitigate the worst of the ravages of a northern European winter. In short, if people started dying in their droves – women and children in particular – France would have a major PR problem on its hands.

“All NGOs have to act on a government invitation,” says Rowan, a Jungle volunteer. “It’s not so obvious in France, but in a place like Syria the reasons for that are clear – they’d be under threat if they didn’t have the say-so of whoever is in power. The French have to invite the UNHCR and they haven’t because they don’t want to admit it’s a problem.”

Apart from MSF, the vast majority of support Jungle residents receive is from tiny charities and less formal volunteer groups. On the way up the main thoroughfare, for instance, we pass numerous caravans brought to the camp by Caravans for Calais, a British charity that encourages people to donate mobile homes. Other charities are there to provide a library of books for children, language classes and basic nutrition.

Order out of chaos

The odd thing is, it just about works. The main road provides the commercial heart, much like the high street in any town in the UK. In the rest of the camp, tents and shacks are established wherever there is space, but there is no sense of jockeying for position closer to water sources or shower blocks. Without formal planning or recourse to property rights, a certain order prevails. As one Sudanese man says: “We come from all over, but we live in peace.”

There is also evidence of a basic market economy. Some of the cafés in the camp may have been set up by charities, but others are migrant-run, and many of the shops, selling everything from fruit to butane gas bearing the mark of French grocery giant Carrefour, are clearly the work of migrant entrepreneurs.

In one shop we encounter an Afghan and an Iraqi working side by side on their hands and knees, rolling cigarettes from a mound of tobacco on the ground. They tell us they set up the shop four months previously and are doing what they can to survive. Further up the road we pass businesses run by Kurds, Afghans, Syrians and more, all rubbing shoulders in this most extreme of national melting pots.

At the end of the day, we encounter two brothers from Sudan, who invite us into a community café for coffee. Ali and Ahmed arrived separately – Ali has been there nine months; Ahmed about six – but both came via Libya and then a people trafficker’s boat to Italy.

For Ali, the journey was particularly traumatic. In broken English he explains that the boat, designed for around 30 but carrying 120 – including children as young as seven months old – ran out of fuel four days into the voyage. After that they drifted without light or any other functioning electrics for a further five days before being picked up by a passing ship.

Yet despite all they have been through, both men are quick to smile and Ahmed, at least, is happy to be photographed. Marcus shows him the pictures on the camera’s LCD screen. “That’s the first time I’ve seen my face in months,” he says.

The lack of mirrors and other basic amenities is underscored by the Iraqi serving up coffee, who comments on the washing facilities in the Jungle. “A three-second shower is all I am allowed,” he says. “There is no time to put soap on. Five men, they say, ‘finish, finish’.”

Their English may be limited, but it is powerful, and Ali and Ahmed have been in the Jungle long enough they are experimenting with wordplay. “We are Jenglish!” they declare happily.

Ahmed adds that he clearly remembers listening to the BBC World Service as a child. “Hello, ladies and gentlemen; this is the BBC in London,” he mimics in his best received pronunciation.

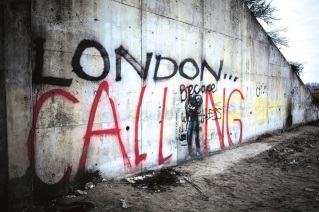

Like all the migrants we speak to, the Sudanese brothers have no desire to seek asylum in France. All the people in the camp want to do is reach the UK. It is why they are there in the first place and explains the widespread graffiti inside and outside the camp. ‘London calling’ declares one piece; ‘We love England’ another.

On the flip side, the contempt for the French state and the police in particular is palpable, with several camp residents alleging police brutality. “The police are fascists,” says one young Eritrean. “My friend went into the centre of Calais and now he is in hospital. No one wants to be in France.”

At that we say goodbye to the Jungle. As the camp disappears in the rear-view mirror, I reflect that despite the frustration of living a life in limbo, the basic sanitation and the daily struggle for dignity, there could be worse places to live. Within 48 hours of our return to London, that assertion will be put to the test.

Claim and counterclaim

Two days after we leave Calais, the bulldozers start moving in, despite the French interior minister’s promises. The riot police – under the provocation of migrants hurling stones – unleash water cannon and tear gas. A young couple sitting atop their meagre dwelling are beaten with truncheons. The authorities claim the woman was threatening to cut her wrists; Jungle volunteers dispute this, saying she was pregnant and that the couple were simply sitting in peaceful protest.

Claim and counterclaim mark the death throes of the Jungle. We have had the wildly contrasting claims of how many people lived there. The authorities said no bulldozers would be used; a promise that was soon broken and that volunteers believe was hollow to begin with. The government also said no one would be forced from their homes – the couple on the receiving end of a baton would probably beg to differ.

Then there is the vexed question of what happens to the newly homeless. The solution the prefecture points to is the north-eastern section of the Jungle, where it had already brought in shipping containers – 124 at my count – to house migrants. From the vantage point of a sandy bluff in the middle of the camp, the fenced-off area appears unpopulated compared with the busy thoroughfare in the Jungle proper.

The problem is that the vast majority of the Jungle’s population do not want to move into the containers – or any other solution offered by the French government. To do so would mean being formally fingerprinted, and remove any chance of applying for asylum in the UK.

The consequence is that many have headed 25 miles up the coast to Dunkirk, where another migrant camp has been established at Grande-Synthe. There, living conditions are reportedly far worse than in the Jungle – and there is none of the Calais camp’s community infrastructure.

“Conditions in Grande-Synthe are some of the worst that I have seen in 20 years of humanitarian work,” says Vickie Hawkins, executive director at MSF UK.

There is the merest glimmer of a silver lining to this cloud. At the start of the year, MSF received permission to build a new camp just 10 minutes’ walk from Grande-Synthe and construction is already well under way. Because it is run by the NGO, many of the restrictions that apply in the shipping containers in Calais and official camps elsewhere in France won’t apply.

The downside is that the permission only allows for sufficient space to house the existing Dunkirk camp. So as quickly as these migrants are moved on, others will take their place in the abandoned Dunkirk slum.

The sad truth is that there is no permanent solution in the offing. The Jungle, for all its faults, at least provided a basic level of sanitation and of community and solidarity established by both migrants and volunteers over many months. By dismantling the Jungle piece by piece, the French authorities may be removing an eyesore and a particularly toxic political problem. But they are only moving it to a less conspicuous site up the coast.

The migrants will still be there, stuck in a country where they don’t want to be, and that doesn’t want them. And with UK politicians – not to mention a large swathe of public opinion – set firmly against intervention, their situation looks unlikely to improve any time soon.

The Jungle is being cleared, but the Jenglish remain

[Source:- Property Week]