The small, Syracuse, New York-based company K-II Enterprises makes a number of handheld electronic devices—including the Dog Dazer (a supposedly safe, humane device that deters aggressive dogs with high-pitched radio signals)—but it is best known for the Safe Range EMF. The size of a television remote, the Safe Range EMF detects electromagnetic fields, or EMF, measuring them with a bright LED array that moves from green to red depending on their strength. Designed to locate potentially harmful EMF radiation from nearby power lines or household appliances, the Safe Range has become popular for another use: detecting ghosts.

Since its appearance in the show Ghost Hunters, where the ghost hunter Grant Wilson claimed that it has been “specially calibrated for paranormal investigators,” the Safe Range (usually referred to as a K-II meter) has become ubiquitous among those looking for spirits. Search for it on Amazon, and many listings will refer to it as a “ghost meter,” an indispensable tool in the ghost hunter’s arsenal. It isn’t alone among EMF meters: Of the best-selling EMF meters on Amazon, two out of the top three are explicitly marketed as ghost meters.

Yet it’s precisely because it’s not particularly good at its primary purpose that makes it a popular device for ghost hunters. Erratic, prone to false positives, easily manipulated, its flashy LED display will light up any darkened room of a haunted hotel or castle. Which is to say, its popularity as a ghost hunting tool stems mainly from its fallibility.

The K-II isn’t the only consumer-electronic item used by ghost hunters. Often it’s sold in kits that contain other devices, such as a Couples Ghost Hunt Kit, with two of everything, so you can build “trust and lasting memories when the two of you, alone in some spooky stakeout, look to each other for confirmation of your findings and reassurance!” There are devices that have been engineered specifically for ghost hunters, like a ghost box, which works by randomly scanning through FM and AM frequencies to pick up spirits’ words in the white noise. But mostly, ghost hunters use pre-existing technology: not just EMF meters, but also run-of-the-mill digital recorders, used to capture electronic voice phenomena, or EVP. An investigator records her or himself asking questions in an empty room, with the hope that upon playback ghostly voices will appear.

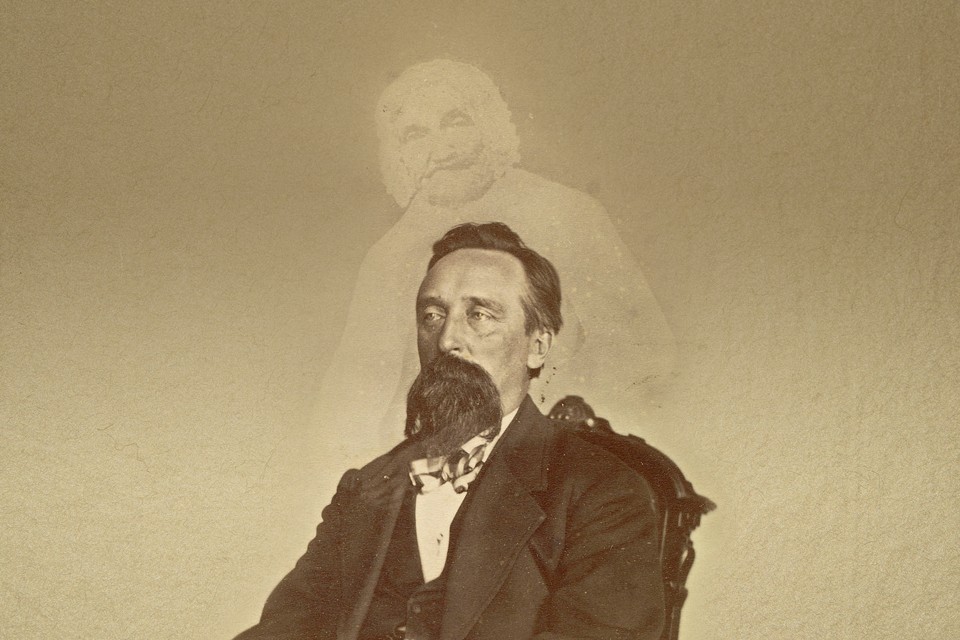

Ghost hunting was born out of a love of technological failure. In 1861, William H. Mumler, a jeweler’s engraver, was studying the new trade of photography when the shadowy figure of a young girl appeared on a plate he was developing. As Crista Cloutier describes in The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult, Mumler knew it to be an error, a consequence of accidentally reusing a plate that hadn’t been sufficiently scrubbed of its previous exposure. But then he showed the curiosity to a Spiritualist friend of his. “Not at that time being inclined much to the spiritual belief myself, and being of a jovial disposition, always ready for a joke,” he later admitted, “I concluded to have a little fun, as I thought, at his expense.”

He told the Spiritualist that the image was authentic, and that no one else had been around when he’d taken the photograph. His friend took the joke all too seriously, and in short order, Spiritualist publications had reprinted Mumler’s mistake as proof of life after death. Mumler himself soon changed his tune, claiming he’d discovered a “wonderful phenomenon that really needed investigation,” and began offering to make spirit photographs in earnest. For ten dollars (normal sittings cost about a quarter at the time), he’d take your photo, with the proviso he couldn’t guarantee a ghost’s materialization.

Mumler’s inadvertent invention of spirit photography cemented a connection between ghosts and technology that endures to this day—and specifically, the ways that mistakes and accidents of technology appear as manifestations of the paranormal. Consumer technologies from photography to telegraphy to radio to the internet are almost always immediately seized on by believers as offering further proof of the paranormal. In 1953, three children were watching Ding Dong School one afternoon on Long Island when the ghostly face of an unknown woman appeared on the screen. The face would not dissipate, even after the television was turned off, and their father was forced to face the television to the wall “for gross misbehavior in frightening little children,” as TheNew York Timesreported. The television died completely a day later, but not before its paranormal nature had made it a minor celebrity.

For Friedrich Jürgenson, it was a cassette recorder. In the late 1950s, Jürgenson, a painter and filmmaker, was experimenting with recording birds in his garden; when he played them back, he heard voices on the tape that he claimed belonged to his dead father and wife, calling his name. After several years refining his technique, he published his findings in a 1967 book called Radio Contact with the Dead. A few years later, a Latvian psychologist named Konstantin Raudive further developed and elaborated on Jürgenson’s techniques, releasing his own book on the science of recording the voices of the dead in 1971.

[Source:- THE ATLANTIC]