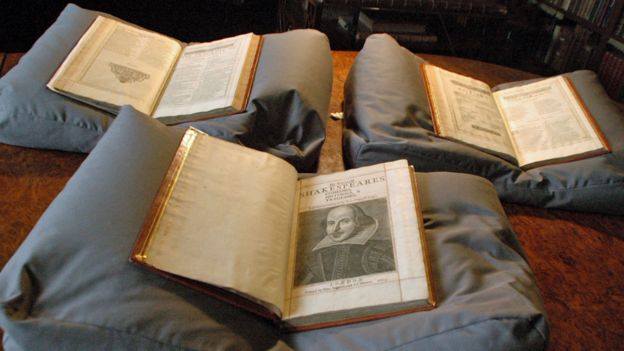

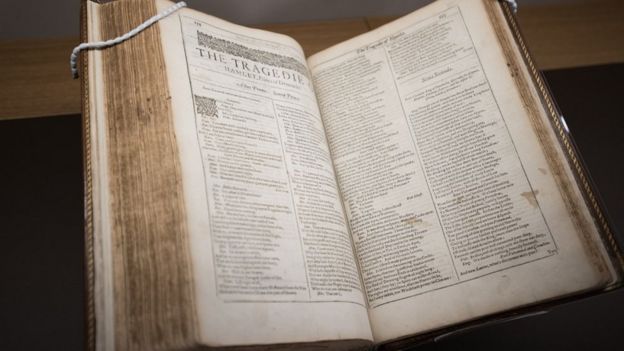

This copy of the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623, was found at Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute

Academics who authenticated the book called it a rare and significant find.

About 230 copies of the First Folio are known to exist. A copy owned by Oxford University sold for £3.5m in 2003.

Emma Smith, professor of Shakespeare studies at Oxford University, said her first reaction on being told the stately home was claiming to have an original First Folio was: “Like hell they have.”

But when she inspected the three-volume book she found it was authentic.

“We’ve found a First Folio that we didn’t know existed,” said Prof Smith.

‘Astonishing’

The goatskin-bound book will now go on public display at the stately home for the first time.

Adam Ellis-Jones, director of the Mount Stuart House Trust, said the identification of this original First Folio was “genuinely astonishing”.

The discovery comes ahead of the 400th anniversary of the playwright’s death.

The First Folio, printed seven years after Shakespeare’s death, brought together 36 plays – 18 of which would otherwise not have been recorded.

Without this publication, there would be no copy of plays such as Macbeth, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar, As You Like It and The Tempest.

The book is also the only source of the familiar dome-headed portrait of Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout.

Printers’ thumbprints

Prof Smith, author of Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book, says it is uncertain how many copies were produced – although some put the figure at about 750.

About 230 copies are known still to exist. The last copy found was two years ago, in what had been a Jesuit library in St Omer in France.

The Isle of Bute discovery adds another, but there is uncertainty about where this copy had spent much of the four centuries since being printed.

It had been owned by an 18th Century literary editor and then appears in the Bute library collection in 1896.

Alice Martin, Mount Stuart’s head of historic collections, believes it was bought by the third Marquess of Bute, an antiquarian and collector, who died in 1900.

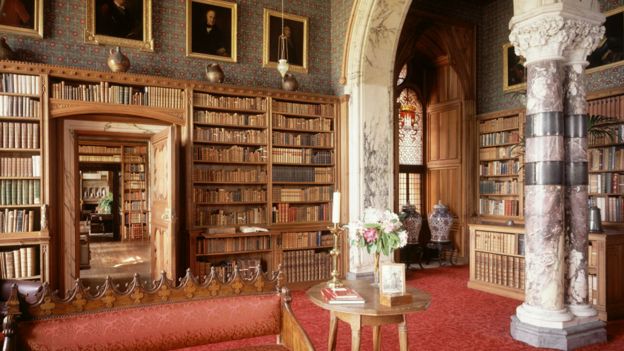

The trust, which runs the Gothic revival house, had been researching the collection of books, paintings and historic items and called in experts from Oxford University to assess the authenticity of what had been claimed as a First Folio.

Apart from its cultural value, verification makes the book extremely valuable. A copy owned by Oriel College, Oxford sold for about £3.5m in 2003, while another copy sold at auction in 2006 for about £2.8m.

Authenticating a copy involves a series of technical checks on, among other things, the watermarked paper and printing process.

Imperfections are also part of the identification, as real copies can include the inky thumbprints of Jacobean printers.

Misspellings also appear, sometimes corrected after proofreading.

Victorian fakes

There is a stage direction in King Lear, which, in the early part of the print run, says rather cryptically “H edis“, which is then updated in later copies to “He dis” before it is finally corrected to “He dies“.

Prof Smith says there are also many fake copies.

Authentications are further complicated by high-quality reproductions produced by a 19th Century craftsman, John Harris.

He was hired by the British Museum to replace missing or damaged pages or sections of old books, including for First Folios – and was so skilled that it is uncertain how much of his work might now be accepted as authentic.

Prof Smith suggests not even all the officially catalogued First Folios may be authentic.

The story of the First Folio, she says, usually focuses on the literary genius of Shakespeare, but the survival of his plays depended on the practical skills of the people who produced this book.

“The vast majority of plays from this period have been lost, because they were never printed,” she says.

The preservation of much of Shakespeare’s work depended on the publishers of the First Folio copying, collating and editing from whatever hand-written scripts and first-hand memories were still available in the 1620s.

As Shakespeare’s reputation grew, the value of the First Folio increased, with the book becoming highly prized by collectors.

In the 19th Century and early 20th Century many copies were bought by US railway millionaires, financiers and oil tycoons.

Mr Ellis-Jones says identifying a First Folio at Mount Stuart indicates how much remains to be examined in one of the “last great unknown collections”.

“We knew that we had special things here, but we keep discovering how special – because it’s never been researched and never been in the public eye.”

Ms Martin says an “abundance of mysteries” remain. “We’ve got completely unexplored collections.”

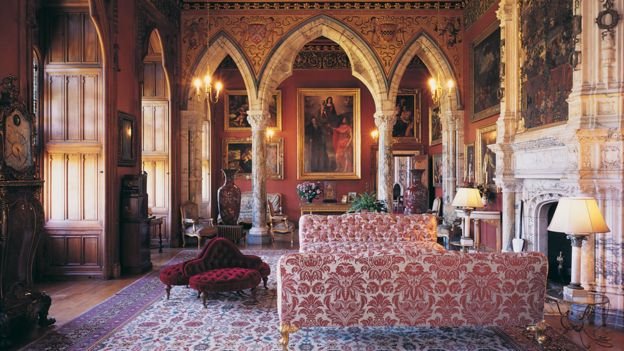

She says there has always been something “quite eccentric” about the house.

As well as being an art collector, the third marquess introduced exotic wildlife to the island, including kangaroos. The last of these exiled marsupials died when it was hit by the island’s first car.

And are any more First Folios likely to appear?

“I’m sure there are a few more out there,” says Prof Smith. “I don’t think they’re in people’s lofts, even though it would be lovely and romantic.

“I think they’re in libraries which have been neglected or forgotten, I suspect more will be in mainland Europe.”

[Source:- BBC]