An entire generation of Syrians has had its education truncated, and the country’s once flourishing academic community has been scattered or driven underground.

The scale of the problem, according to the president of the Institute of International Education (IIE), Allan Goodman, is “unprecedented” in the near 100-year history of his New-York based organisation.

Higher education in Syria was expanding on the eve of the conflict in 2011, with some 350,000 full-time undergraduates and more than 8,000 lecturers and professors.

More than a quarter of young people were going into higher education.

Five years later, around 2,000 academics and hundreds of thousands of students are living in the refugee camps of Turkey and Jordan.

Many more are lost among the millions of internally displaced Syrians.

“Even in Iraq, when professors were being assassinated and there was terrible violence, many universities managed to stay open, and many students continued to study,” says Mr Goodman.

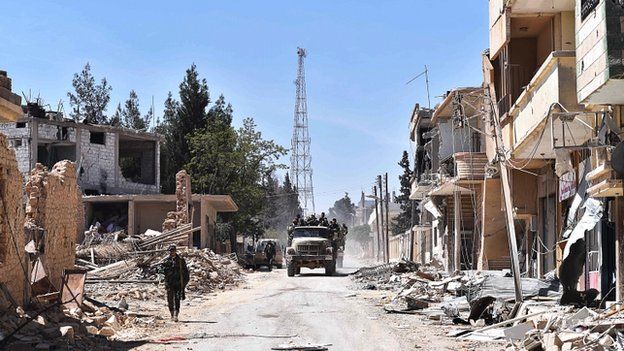

But in Syria, universities were often deliberately targeted and destroyed.

Mr Goodman says the international community has only recently started to appreciate the gravity of the problem – and the need for higher education to be part of any rebuilding and post-war reconstruction.

The IIE has been working to rescue scholars from Syria and to help refugees.

Sana Mustafa is now a final year undergraduate at Bard College in New York.

She had been a business student in Damascus and had been detained by the Syrian secret police after taking part in an anti-government demonstration in 2011.

She was released and in 2013 went to Lebanon to take part in conflict resolution and peace-building workshops.

While there she won a place on a US-Middle East programme at the Roger Williams University in Washington DC and arrived in the US in the summer of 2013.

“I was supposed to stay two months, but while here my dad got detained in Syria.”

“I couldn’t go back. My mum and two sisters fled to Turkey. I had been in my fourth year, I had nearly finished, just one a semester left, but I couldn’t continue with it, because first I had to survive.”

“I was trying to find shelter, a ceiling to sleep under, and to get political asylum.

“I started moving from place to place. I stayed in nine places in one year, always couches, I never had my own bed. I was staying with random people, I knew no one, I had no money, I mean it, nothing.”

The IIE were able to help her to apply for scholarships – and her current college offered her full funding.

Dr Talal al Mayhni, a neuroscientist at Cambridge University’s Department of Clinical Neurosciences, left Syria in 2011.

“As a Syrian, all I can say is we lost control of what is going on in our country… I am not wanting to blame anyone.

“I think there are a reasonable number of scholarships available to support Syrians. But there are lots of obstacles, and it’s not just the academics. You have the postgraduates and undergraduates who have lost years of their lives.”

“It has affected a whole generation.”

As for his former university, Dr al Mayhni hears: “There are informers everywhere. It’s not a place for academic excellence any more, sadly.”

Another Syrian academic at a UK university, who wished to remain anonymous, said that at Aleppo University, things got to the point where “there was no electricity, and it was often difficult to find water. But we did our best”.

Staffing of his faculty reduced from nearly 60 to 10 and most of his male students had been forced to join the army.

More stories from the BBC’s Global education series looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

But there are some glimmerings of light and initiatives to pluck a few more Syrian scholars from the furnace.

The IIE’s Scholar Rescue Fund and the Finnish government’s Centre for International Mobility (CIMO) has launched a scheme to allow Syrian scholars to continue their work in Finnish universities.

Selecting the students can be difficult.

“It’s a very challenging and sensitive process,” said James King, assistant director of the IIE’s Scholar Rescue Fund.

As with any scholarship application, they’re asked to supply CVs, references, samples of publications – but for many, meeting these requirements is impossible. Documents are lost or withheld, referees can be gagged by hostile institutions.

The joint project with Finland will add a few more rescued academics to the 83 from Syria and 304 from Iraq awarded fellowships by the Scholar Rescue Fund.

The Council for At Risk Academics (CARA) is the direct descendant of the Academic Assistance Council founded by William Beveridge, director of the London School of Economics, in 1933 to help academics suffering under Nazi persecution.

It has since had many changes of name – but its job is essentially the same, and it has never been short of work.

“Our founders were very clear, their mission was in two parts: the relief of suffering, and the advancement of learning and science, ” said Stephen Wordsworth, executive director of CARA.

“Certainly the Syrians we’re helping are quite clear they want to go back to help build a better society when that’s possible”, he added.

“It’s very much the way they think. A couple of years ago we were having the same experience with Iraq, and 90% of them did go back”.

There were cases of academics who returned to Mosul, in northern Iraq, and then had to leave a second time after its occupation by the so-called Islamic State group.

Assassinations of professors in Iraqi cities, alongside the murder of the Palmyra archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad in 2015, raised awareness of the desperate situation of scholars.

“Higher education is a very international business, and there’s an awareness of our responsibilities to our peers,” Mr Wordsworth added.

CARA works with a network of 113 universities in the UK. Their support to help Syrian scholars, in terms of fee waiver and living costs, increased to over £2m in 2015.

“They are all trying to help,” said Mr Wordsworth.

The academics who have found sanctuary abroad have cast light on conditions for those still trying to work in Syria.

“Some universities are still operating, some have shut down altogether,” Mr Wordsworth said.

Simply getting to work could be perilous: “They find themselves going through multiple checkpoints run by assorted militias… they get robbed, they get dragged away to join the army… or they just get beaten up.”

The biggest efforts to help displaced Syrian scholars have come from Germany.

In 2014 the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) won government funding of 7.8m euro (£6m) to offer 200 scholarships. It received over 5,000 applications, half from academics still in Syria.

“We put together a travelling selection committee of 25 German professors”, said DAAD’s Middle East region head Dr Christian Hulshorster. “We travelled for three weeks, interviewing in Istanbul Beirut, Cairo and Erbil.”

Image copyrightReuters

Image copyrightReutersThese students, mostly postgraduates, are now studying in German universities.

There are also science research fellowships named after Jewish pathologist Philipp Schwartz, who fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and founded the Emergency Society of German Scholars Abroad.

Another German 100m euro (£80m) initiative has been launched this year, to help refugees who were already in, or about to start higher education back home.

DAAD’s secretary general, Dorothea Ruland, said these students were important as they would eventually return to Syria and inspire future generations.

Mr Goodman says if he had a “magic wand” he would create an entire university in exile.

There have been two examples of this – the New York School for Social Research, funded by the Rockefellers in 1933, and the European Humanities University, opened in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2005, in exile from Minsk in Belarus.

But with the political debate on refugees becoming heated, the idea of rescuing scholars is getting tougher.

There have been questions about the morality of offering sanctuary to professors while others are left to the mercy of traffickers.

It’s not an argument Mr Goodman accepts: “We need a change of mindset… We know that refugees spend many years in camps, and to have a whole generation growing up in a camp with no education is a very dangerous thing.”

[Source:-BBC]