Over the past few days, our inboxes have been flooded with letters from doctors and medical researchers whose lives have been shaken up by President Donald Trump’s executive order, which, among other things, restricts immigrants and visa holders from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US.

We’ve heard from foreign-born health care workers who are trapped inside the United States, and from those who can’t enter, despite having jobs, research positions, and US visas or green cards. It’s gut-wrenching.

But the chaos unleashed by the executive order also reveals a little-appreciated fact about our health care system: We’re heavily reliant on foreigners. They’re our doctors, nurses, and home care aides, and they often work in the remote places where American-born doctors don’t want to go.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7912267/immigrant_doctors_us_health_chart_vox.png)

In many ways, the health system is already stretched too thin, with scarcely enough people spread evenly across the country to do many difficult jobs. And in letter from the American Medical Association to the Secretary of Homeland Security today spelled out how Trump’s immigration policy could make this worse by “creating unintended consequences.” As AMA CEO James Madara wrote:

“Many communities, including rural and low-income areas, often have problems attracting physicians to meet their health care needs. To address these gaps in care, [international medical graduates] often fill these openings.”

Indeed, it’s now clear that health care is going to suffer as a result of the immigration ban, particularly if the current restrictions are broadened to include more countries or different types of visas, as is expected.

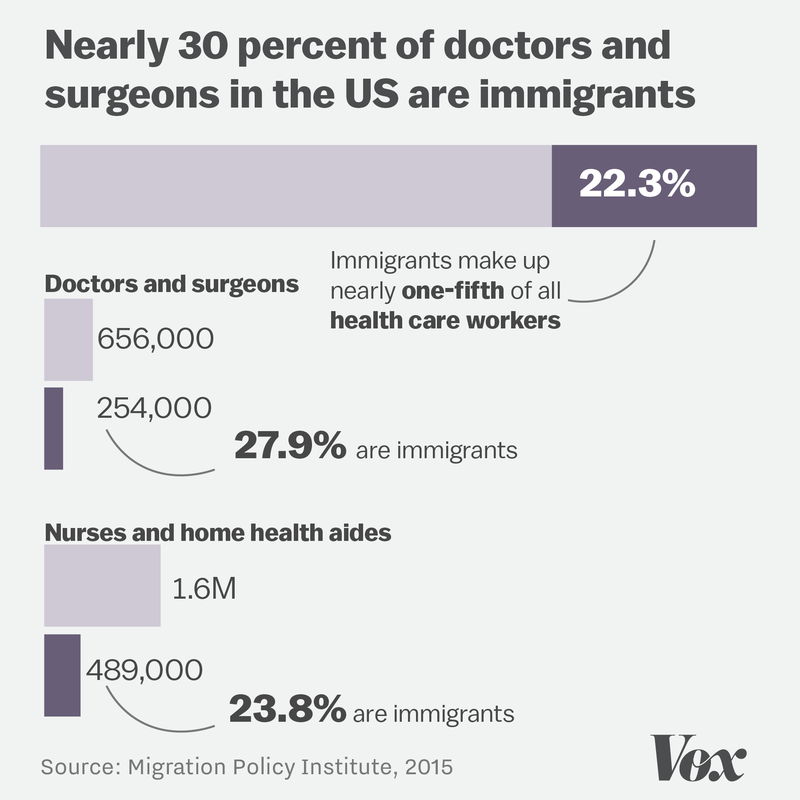

Immigrants make up 22 percent of the health workforce and 30 percent of doctors and surgeons in the US

The health care workforce in the US is a lot more international than you might think. Health care currently has the largest proportion of foreign-born and foreign-trained workers of any industry in the country.

According to 2015 data from the Migration Policy Institute, the medical profession is particularly reliant on immigrant doctors. Of the active physicians and surgeons here, 30 percent are immigrants.

“India, China, Philippines, Korea, and Pakistan are the top five origin groups for physicians and surgeons,” said Jeanne Batalova, a senior policy analyst and demographer at MPI. But Iran and Syria, two of the seven countries whose citizens are no longer allowed entry to the US, are the sixth and 10th largest contributors, respectively. “So we’re talking about substantial representation from these countries [in the doctor workforce] here.” The ban on these people will likely be felt at hospitals and clinics across the nation, she added.

The contributions immigrants make to medical care start early on, in residency programs, which funnel doctors through training and into jobs. Residents from the seven countries made up 5.7 percent of all international medical graduates in 2015, said Stan Kozakowski, a doctor and the director of medical Education for the American Academy of Family Physicians.

(Some data sets look at the country of origin for doctors, others at where they obtained their medical degree — and doctors who trained outside of the US are called “international medical graduates.”)

That’s not a huge number right now, Kozakowski added, but it’s sizable enough. “And if you add in the countries that have been tossed in as possible expansions of the ban — Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Egypt — that number goes up to 16.7 percent.”

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7913989/immigration-us-doctors-map-vox.0.png)

When you look at the numbers by medical specialty, foreign-trained doctors do a disproportionate amount of the work in many areas. They make up more than 50 percent of geriatric medicine doctors, almost half of nephrologists (or kidney doctors), nearly 40 percent of internal medicine doctors, and nearly a quarter of family medicine physicians, according to data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Compared with US-trained physicians, foreign doctors are also more likely to practice in areas where there are doctor shortages — in particular, in rural areas, as the AMA suggested. (Many enter the US on visas that allowed them to stay if they work in an underserved area for three years after residency.) They’re also more likely to serve poor patients on Medicaid, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7912281/immigrant_doctors_us_health_specialties_chart_vox.png)

“Doctors — especially in rural areas that were the key consistency that supports Trump — tend to be foreign-born,” said Nicole Smith, a chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “The old adage that foreigners are doing the work no Americans want to do even applies to medical doctors.”

Health care currently has the largest proportion of foreign-born and foreign-trained workers in the country of any industry

The foreigners in health care don’t just practice medicine, though. The nursing profession is also overstretched and facing projected shortfalls in the coming years, and has come to count on immigrants. Some 20 percent of the health care support staff — including nursesand home aides — were immigrants as of 2015.

Besides work at the bedside, the research immigrants do in labs across the country is also under threat. One Syrian medical researcher told Vox he’s afraid that after working in America for more than three years at the Mayo Clinic, his application for permanent residency will now be rejected and he’ll have to leave. Other researchers on visas and green cards from Iran told us they fear leaving the US to visit family or go to conferences should they be barred from coming back home, and that this situation was untenable and had them thinking about alternative places to live. So from bench to the bedside, Trump’s approach isn’t just going to hurt the health system in the future — it already is.

[Source:-VOX]